Flexibility is as old as humanity itself. It’s been proposed over and over again throughout architectural history. Talking about “flexible architecture” means envisioning a design that allows a building to shift in shape and use throughout its lifetime.

But… how far can we take it?

From the creators of less is more, less is a bore, and yes is more, here comes: flex is more (?)

Is flexibility the next cool thing?

To start, we could break it down into two types:

One that lets the entire building adapt inside and out (external flexibility) and one that only reshapes the interior layout while the structure stays fixed (interior flexibility).

External Flexibility

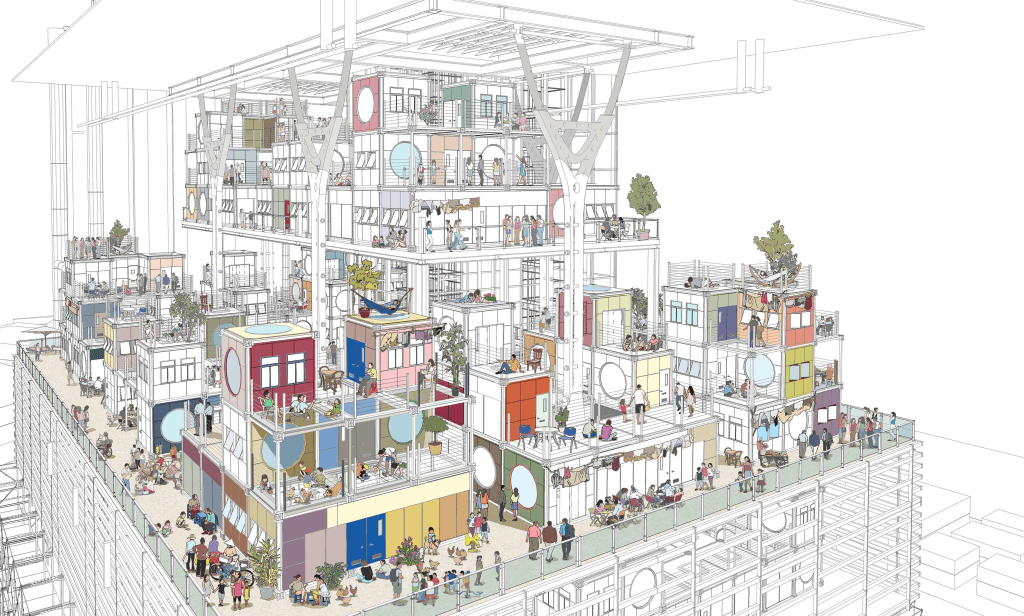

Back in the 20th century, the Japanese Metabolists imagined cities that could grow organically based on the needs of their residents. The “Nakagin Capsule Tower” (1970) followed that logic: a single structural core with plug-in capsule units that could be added or removed as needed.

In practice? No capsules were ever added after the initial build. (Spoiler: it was demolished in 2022.)

That concept inspired prefab housing with shipping containers and modular units… but the dream of growth, variation, or long-term adaptability mostly stayed on paper.

Same fate for David Fisher’s “Dynamic Tower” (2008), which proposed a central core with spinning apartment units that rotated based on weather or personal mood.

Never built.

On the other hand, Chilean Pritzker-winner Alejandro Aravena got way closer to true adaptability—without the spectacle. In “Quinta Monroy” (2004), only half the house was built (bedroom, kitchen, bathroom, and rooftop), leaving the other half up to the future homeowner.

Unlike the other examples, this wasn’t about showing off some flashy new way to do architecture—it was about giving people control and flexibility over their own space.

But Quinta Monroy showed us flexibility has an expiration date. At some point, the house just stops changing.

Interior Flexibility

Office buildings with open floor plans are probably the peak of Modernism’s flexible vision. A fixed service core (elevators, ducts, staircases) gives tenants total freedom to rearrange interior partitions as needed.

And it’s not even considered a cost—it’s an investment. Open spaces, no walls, beanbags, hammocks, ping-pong tables, and beer fridges. Google-style flexibility.

But that’s another story.

When it comes to residential interiors, things get trickier. Especially when we’re talking about minimal housing. Designing flexible spaces in a 10,000 sf house with a garden? Easy. But doing that in a 850 sf apartment with 3 bedrooms and an “open kitchen” meant to make the living room look bigger.

That’s a different game.

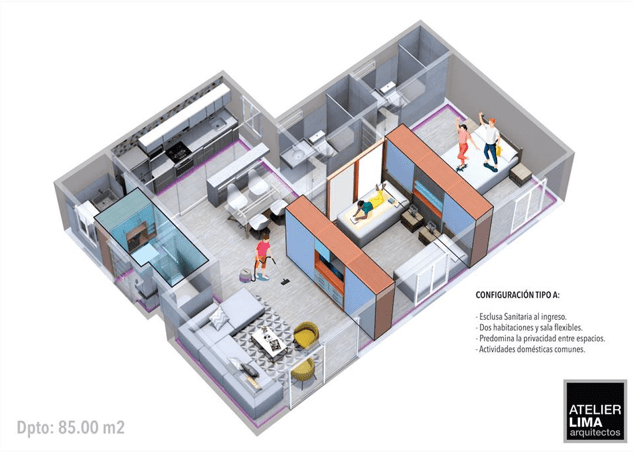

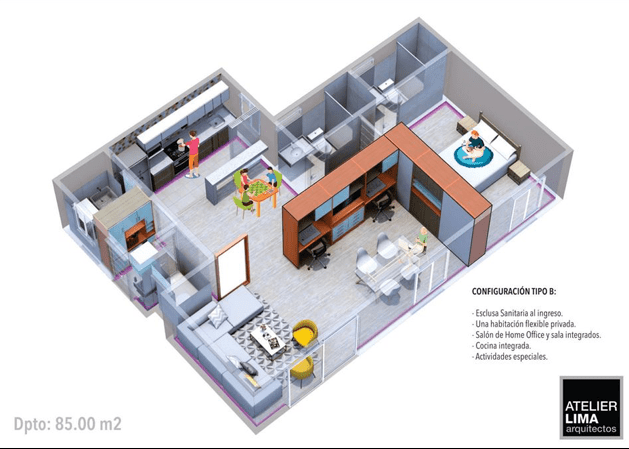

Atelier Lima (2020) came up with small apartment modules that let you, say, turn a secondary bedroom into a larger living room by shifting a couple of closets around.

These solutions seem practical. But let’s be honest—beyond the Murphy beds, convertible sofas, and foldable dining tables-turned-desks, these designs often end up as flashy marketing tools masking the real issue.

Because what they’re actually telling you is:

“Since your bank loan won’t cover more square footage, here’s a system where you can collapse your kid’s room every time you want to host a dinner party.”

Is that the goal of residential flexibility?

The real issue, in my view, lies in how little space we’re actually giving people to live. It’s no surprise the market is flooded with smaller and smaller apartments—“just like the big cities!” they say.

And in that context, flexibility is just a band-aid. It squeezes more out of a shrinking space without addressing the root of the problem.

Hopefully, the Covid-19 pandemic pushed us to rethink what housing should be—starting with regulations that guarantee dignified living space: side setbacks, cross ventilation, renewable energy, natural light, open spaces, and more.

In the end, flexibility in architecture isn’t inherently good or bad—it’s a tool. But when it’s used to mask poor spatial planning or to justify ever-shrinking living conditions, it loses its value. True flexibility should empower people, not compensate for market-driven limitations. If a space doesn’t work in its simplest, most static form, no amount of folding walls or sliding panels will save it. Architecture isn’t about chasing trends—it’s about creating spaces that endure, adapt with dignity, and serve real human needs.

Leave a comment